Some 'Dutch' Culture Orientations

J.K. Mellis (1999, revised in 2017)

This article is based on a paper I wrote for one of the courses at the VU University in Amsterdam that I followed toward receiving an MA in Cultural Anthropology (2005).

In his book, Culturen Bestaan Niet (Cultures Don't Exist), van Binsbergen (1999) clarifies the meaning of the title. ‘Cultural characteristics only become visible in communication with others’ (emphasis mine). It is in this sense that the characteristics of 'Dutch culture' will be described in this paper. Expatriate visitors and new immigrant peoples from a variety of cultures, if able to converse with each other, are still likely to identify certain Dutch 'cultural orientations' from common experiences they have had in communication with Dutch people—those who have been socialized from early childhood in Dutch families and society. What I, and other immigrants have seen is consistent with the observations made by 'native Dutch' people who have returned from a period of sojourn in another culture. It is hoped that 'native Dutch' people, and other longer-term residents of the Netherlands who have themselves taken on various Dutch 'cultural orientations', will also be able to recognize some of these in the way they communicate with expat visitors and foreigners who are still strongly identified with other cultures.

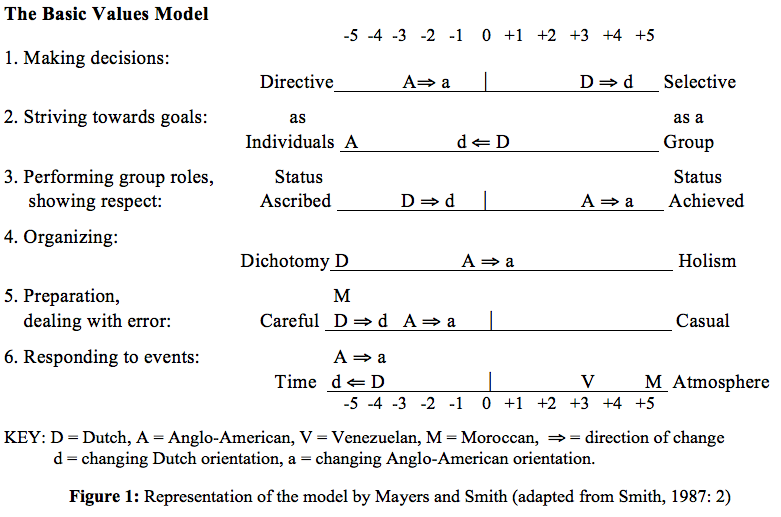

This essay first attempts to identify some of these Dutch 'cultural orientations' with the help of a communication model developed by Mayers and Smith. The model was originally developed to help a visitor or immigrant in a new culture identify potential or real areas of tension between the 'cultural orientations' of his own social background and that of the new society in which he or she must learn to live. But as the model was also developed to increase the self-awareness of the person using it, it is also useful for members of a host society in their communication with visitors and immigrants. In this paper, I will use the model as later adapted by Smith, though the normal order of the 'continuums' has been rearranged to highlight the differences I faced when comparing my 'Anglo-American' orientations with those of the Dutch society I was entering.

The model is divided into six interactional aspects of group life common to all societies, in other words, how people tend to: approach and make decisions; strive toward goals; show respect and perform group roles; organize activities and ideas; deal with error; and respond to events (see figure 1).

Each of these aspects is presented as a continuum between two different extremes, measured from one side (-5) to the other (+5). Since the descriptions in this essay are more based on impressions and anecdotes than on research statistics, only the numbers 1,3 or 5 on either side of the continuum will be used—to indicate a week, moderate or strong orientation.

Identification of such 'cultural orientations' can be a great help to the visitor or immigrant who wishes to improve his own communication with people in Dutch society. At the same time the newcomer should keep in mind three things: no culture is static, real cultures are diverse, and the 'cultural glasses' with which he or she grew up color the observations and experiences of the newcomer. The same can be said for the intercultural observations and experiences of those ‘native’ to the 'host' Dutch society. In the second half of this essay I will discuss the limitations and usefulness of this analysis of Dutch cultural characteristics.

After reading this article, you can learn how I applied this model when building relationships with neighbours from Middle Eastern cultures, by clicking on 'Video Teaching by Jim Mellis' and then scrolling down to the 7-part lecture I gave on 'Some Dutch Cultural Orientations' in Zandaam, the Netherlands (7 April 2017).

1. Some Characteristics of a Dutch Cultural Orientation

Responding to events

In the Netherlands, events are oriented around the purpose and passage of time. The beginning, duration and ending of events are thus determined by the clock—an ever-present object in most places where people gather. And most people wear a watch. While an event may vary in length, those present are usually more tuned to the passage of time than to the atmosphere. Beginning and ending times are noted in advance in agendas and are usually strictly followed. Children in elementary school are taught the importance of being 'on time' and of using an agenda. While clocks and agendas govern the 'work' aspect of social life, recreation (in clubs) and celebration (like at birthday parties) are aspects of life which are governed more by atmosphere (gezelligheid) than by time. Likewise, art and atmosphere are nevertheless considered important in public spaces. Thus Dutch culture is only moderately oriented towards 'time' (-3), though the international business orientation of the culture in a competitive global economy appears to be strengthening this orientation.

People in Anglo-American culture, though not as strict about beginning and ending times, are still highly time-oriented. Yet while this orientation appears to be driven in the Netherlands by a preference for organization, in Anglo-American culture it seems more driven by an emphasis on individual achievement. This drive for achievement often makes their recreation and celebration events just as governed by the clock as their work times. Thus Anglo-American culture is strongly time oriented (-5), though change seems to be in the opposite direction of Dutch culture.

In contrast to both Dutch and Anglo-American cultures, Venezuelans and Moroccans both place a much greater emphasis on atmosphere during events than on the passing of time. Their gatherings are generally characterized not only by imprecise beginning and ending times, but also by larger quantities and varieties of food, special clothing and emotional speech.

A preference for organization and dividing things

The strongest characteristic in a Dutch 'cultural orientation' appears to be the high level of organization. Respect is given if you fit into a place in the system. Education is structured to help youth find their place. Early training in the arts and sports (except for swimming) is generally separated from academic education. Public roads are divided with different spaces for pedestrians, bicycles, waiting taxis, parked cars, moving cars, public transport lanes and pedestrian islands at tram and bus stops. Time is divided and organized in agendas, according to purpose: work, discussions, conversations, recreation and parties. Communication on the street or in public transportation is limited as people are usually in between purposed activities. People and things are categorized for easy reference. Ideological conflict has been dealt with traditionally by the division of society into various ideological 'pillars'. Though this is changing, vestiges of this system still remain. Public figures are expected to keep their private lives private, and in public discourse emotional content is divided from rational content and removed as much as possible.

In Anglo-American public discourse, emotional expressions (a politician's tearful account of sexual misdeeds) share the stage with rational discussion of issues. Both personal qualities and educational qualifications are considered relevant in a job interview. Schooling includes not only academic study, but various voluntary societies and sports teams as well. Athletics are also seasonal rather than year round such that students are not limited to participation in only one sport. Though a 'major' field of study is required in most post-secondary schooling, the emphasis is still on a general education in ‘liberal arts and sciences’.

Dutch society can be said to be strongly 'dichotomous' (-5), with little apparent change evident. Anglo-American culture, in spite of its more 'holistic' tendencies, is still strongly influenced by the more 'dichotomous' disciplines of scientific study and technological developments. Moderately 'dichotomous' (-3), it appears to be moving more toward 'holism'.

Decision making

In the Netherlands there seems to be a strong expectation that each individual will have his or her own opinions and take responsibility for his or her own actions. Both at home and at school, children and youth are allowed, even encouraged to express their own opinions. In elementary school they are given agendas in order to record any assignments. The traditional method of queuing up in a shop still involves each person knowing who came into the shop before him. When buying a car it is the responsibility of the buyer to inform the particular tax authorities of the purchase.

My teen-age children have commented on how they have felt more 'equal' treatment from adults in the Netherlands than in either English or Anglo-American cultures. In the latter two contexts they felt that less was expected of them and that their opinions were not yet seen as important. While this also relates to role and status differences, it also reveals a priority in Dutch culture to encourage the development of individual responsibility. A young person who is mondig (mouthy) in an English or Anglo-American context is more likely to be thought rebellious than in a Dutch context. In fact, onmondig (not mouthy) traditionally also indicates someone who is a minor, i.e. an underage child. In the Netherlands it is important to be able to stand up for yourself (je moet voor jezelf opkomen).

Group decision-making processes reflect this orientation, as decisions in business and government are usually arrived at only after much discussion (overleg) in which the opinions of a wide variety of involved individuals and interest groups have been consulted. While expert viewpoints may be presented, the cooperation of all affected by the decision is insured by allowing adequate opportunity for each individual or interest group to be heard.

Therefore, the Dutch can be said to be moderately 'selective' (+3) while the Anglo-American culture appears to be moderately directive (-3). Both cultures seem to be changing in the direction of greater selectivity in decision-making (see figure 1).

Striving for goals, benefit when goals are reached, 'bescheidenheid'

Are goals set by individuals or by a group? Who benefits or is disadvantaged when goals are reached: the individual or the group? Because individual responsibility is considered so important in the Netherlands, most personal goals are set by each individual. And much work is carried out individually. However, in the striving for and achieving of such goals it is also important that the individual not stand out, and that others not be disadvantaged. Personal wealth is okay, but it should not be accompanied by ostentation.

Both the high levels and gradation of taxation, and the system of social security reflect a concern that the weak share at least some of the benefits of prosperity and not be disadvantaged by the achievements of the strong. Codes of modesty ('bescheidenheid') also govern public discourse. Presentations that are self-promoting or over-emotional are considered disadvantageous to others involved in the decision-making process and in the pursuit of group goals. The education system is designed to help each individual discover a place where he or she can best contribute to society. Though marks are given, demonstration of the ability to do the work (passing) is more important than excelling. ‘Just act normally, then you're already acting crazy enough’ (Doe maar gewoon, dan doe je al gek genoeg!).

In Anglo-American schools, students are encouraged by a system of marks and prizes in order to encourage excellence. Emphasis is on competition, on seeing how far each individual can go, and on stimulating individual achievement. Thus, self-promotion and emotion play a greater role in public discourse.

The Dutch, therefore, appear slightly group oriented (+1) in striving toward goals, though this orientation seems to be changing slightly towards the individual side (-1). Anglo-American culture is dominated by a strong individual orientation (-5) in striving toward goals. In spite of the rhetoric of the 1960s and 'generation X' this doesn't appear to be changing.

Status and performing group roles, pragmatism

Finding a 'work' role and playing it well has traditionally been the most important goal in primary and secondary education in the Netherlands. While greater respect is given for some professions (doctors, national politicians, executives of well-known companies, etc.), anyone who has a recognized (defined) role, and who works hard at that role, receives respect. Youth who are not busy studying (taking a year off) or immigrants who are not working and/or studying Dutch (but collecting unemployment benefits) are tolerated but not respected. Students of mine from Venezuela noticed that when they identified themselves as 'students', they received increased respect from Dutch people. When they identified their place of study as a 'university', they noticed non-verbal expressions of increased respect.

A thirty-five year old colleague studying at the University of Amsterdam was mistaken for a teacher during a student strike and obstructed by fellow students from entering a university building. Why? His bag (tas) resembled bags common to faculty members, not bags common to students. Women, though more representative in middle management positions over the past thirty years are ‘still a rarity on boards of directors’ (van der Hoorst 1998: 87). ‘Netherlands has the fewest number of women in top positions (in business)’ compared to other countries in Europe and the western world. This Dutch woman, raised in the USA and filling top leadership roles in business there, found on moving to the Netherlands to work five years with Phillips that she was the first woman in the top positions she filled—for ‘male-female distinctions are less traditional in the USA’ (Spek 2005: 6).

In Anglo-American culture, the American dream (‘anything is possible’) has had a strong effect on both occupational practice and the educational system. Almost everyone goes to the same kind of secondary school, and most Anglo-Americans go to a college or adult education of some kind at some time in their lives. Respect is given to those who 'go the farthest' and those who win. Prizes, contests and scholarships are won by those who get the highest marks and are involved in the widest variety of volunteer activities. Yet this strong 'achievement' orientation is still strongly mitigated by the traditional attitudes and realities of racial hierarchy.

The Dutch, therefore, can be said to be moderately 'status ascribed' (-3), though this orientation is weakening. Anglo-American culture appears to be moderately 'status achieved' (+3). Yet with increased opportunities for racial minorities in recent years, this orientation seems to be growing stronger.

Planning to avoid error

Significant 'cultural' errors involve: acting immodestly (onbescheiden), being unreliable or dishonest. Not having a recognized place of study or work in society, or disadvantaging others by not playing ones role, are also serious errors. Decisions made without adequately inclusive discussion is another. Such errors should be avoided by foresight and planning. Failure to foresee potential negative consequences to oneself or to others is treated as a serious error as well. Warning others, when their behavior is perceived to invite negative consequences—usually in children, students and immigrant newcomers, but often in other 'Dutch' adults as well—is common. The ability to defend oneself in the face of such criticism appears to be one 'rite of passage' into adulthood.

Such warnings are often taken by immigrants and visitors as personal attacks (Dutch bluntness?). Their expectation that criticism should be softened or delivered indirectly no doubt says as much about their own cultural orientations as it does about the Dutch. In Anglo-American culture, a well-intentioned warning is often cushioned with euphemisms or balanced with some form of emotional encouragement, something likely to be considered superfluous or dishonest by a Dutch person.

Dutch people, therefore, can be said to have a strong 'careful' orientation (-5), though this trait seems to be moderated among younger people and in cosmopolitan urban settings. Anglo-American culture appears only weakly 'careful' (-1) and changing in the direction of being slightly 'casual' (+1).

Some cultures, like that of our Moroccan friends, also have a 'careful' orientation, but 'deal with error' in a different way than in 'Dutch' culture. Instead of planning to avoid error, the emphasis seems to be more on covering it up when it occurs, or in blotting it out. Personal mistakes are mostly denied or explained away. And when certain errors occur that would bring serious shame to the family, the family member seen to cause it is disowned and pressured to relocate to a distant city so that the local honor of the family is maintained. Thus, traditional 'Moroccan' culture can also be said to have a strong 'careful' orientation (-5), though for different reasons than in 'Dutch' culture.

2. Critique of the Basic Values Model

Descriptive goals and ethnocentrism; academic instruction versus social adaptation

Most of the above descriptions of Dutch 'cultural orientations' have been based on personal experience. This personal experience has also been informed by reading Dutch authors and by listening to Dutch acquaintances and friends. Such readings and discussions have provided an insider's perspective to balance my observations as a recent immigrant.

These observations were made using a particular descriptive model, a model designed to enhance the social adaptation of a sojourner to a new society: in my case, an Anglo-American seeking to adapt to life in the Netherlands. People who merely study another culture as students, on the other hand, will have limited opportunities for long term immersion in another culture. For most of these students, their exposure to other cultures will be limited: to what they read about other cultures in books, and to the instruction they received from their teachers and professors. And both the reading and the instruction usually takes place in their own mother tongue (e.g. English) and with the limited goal of ‘getting an education’ or a university degree. Any personal exposure they might have to people of other cultures will most likely also be limited: to selected acquaintance with foreigners living in their own social context (their home country or a transnational community like my own organization, Youth With A Mission), or to brief encounters during short travel experiences.

Without a longer-term immersion experience in another culture, however, much of the discussion about culture and cultural differences remains conceptual. Written descriptions of a culture could be mere cultural 'ideals', or they might be 'ideas' which are unrepresentative of the culture since, ‘what most people think is likely to be different from what the most famous artists and intellectuals think’ (Nussbaum, 1997:127).

The 'basic values' model used in the above description of Dutch culture was developed by two Anglo-Americans: Mayers and Smith. The former lived for an extended period of time in a Latin American country, the latter in Columbia, Ethiopia and Spain. The model was developed to help long-term sojourners gain understanding of various cultural orientations—their own and that of the new society—in order to increase adaptation and participation. Thus, it can help a sojourner avoid both pitfalls of chauvinism (or ethnocentrism) and romanticism, because it focuses on six areas common to all societies: ‘spheres of life in which human beings, wherever they live, have to make choices’(Nussbaum 1997: 138).

The model as used in the above description of Dutch 'cultural orientations' also avoids these pitfalls through functioning in two directions. While enabling the newcomer to gain a greater awareness of the cultural orientations of the people in the new society, it also helps him or her gain greater self-awareness concerning the cultural orientations of the society in which he or she grew up. This self-awareness is useful not only for contrast and comparison, but for self-understanding during times of stress. When experiencing stress, the sojourner is most inclined to retreat to the safety of ethnocentric descriptions and judgments, based on his or her own 'native' cultural orientations.

Because the model was developed by two fellow Anglo-Americans, it is possible that the model itself—and my use of it—is descriptively ethnocentric. For example, it bears the marks of Anglo-American organizational preference for using 'dichotomy'—through the use of polar continuums. I have found that students of mine who come from more 'holistic' cultures often like to identify themselves at '0' on the continuums—neither on one side or the other. Though this is a potential weakness, it is less so in this study since both Dutch and Anglo-American cultures appear to be comfortable with organizing things by 'dividing'.

Romanticism, tradition and variation

‘Pithy’ descriptions of another culture are problematic because they overlook several important factors. Besides the danger of oversimplification, pithy descriptions based on personal experiences don't adequately account for diversity within a culture. ‘Cultures are plural, not single’ and 'have varied domains of thought and activity’ (Nussbaum 1997:127). It is therefore difficult, in a three-page description especially, to encompass such plurality. An attempt was made when discussing the role of time and atmosphere in social 'events' to show how the same people might respond differently if an area of life is defined by personal rather than work relationships. A longer essay would also need to account for differences: between urban and rural populations in the Netherlands, between young and old, and between indigenous and recently naturalized citizens. Nevertheless, the use of continuums does lend itself to identifying how the variations within one culture might still form a 'cluster' that occupies a different range on the continuum than the 'cluster' formed by the variations of another culture.

‘Real cultures have a present as well as a past’ (Nussbaum, 1997:128). Thus, a profile of a culture can be too easily skewed by a picture that is either too traditional or too modern. Too much emphasis on tradition leads to a mystical 'romantic' picture that is too neat, one which doesn't take into account either internal variations or the ongoing process of change. In the diagram on page 1, and in the descriptions of five of the basic value areas, an attempt was made to show the direction of cultural change. Modernization, secularization, globalization and pluralization are all affecting the cultural orientations of both Dutch and Anglo-American cultures. Noteworthy though, is the relative absence of change perceived in what seems to be a dominant continuum in each culture. The Dutch appear to remain very dichotomous in the way their thinking and in their social organization, while Anglo-Americans seem to remain highly focused on accomplishment through individual effort.

One reason I have focused on describing only Anglo-American culture is that in the broader American society, historically, there has been a strong differentiation of people by 'race'. As a result, large segments of American society have developed preferences of interaction different from that of the dominant 'English-based' cultural tradition that absorbed most of the European immigrants, including my Dutch ancestors. This differentiated development, together with increasing urbanization and the large waves of immigrants from non-European nations during the 20th century have led to what some call a 'multi-cultural' society. Over the past sixty years, Dutch society has being affected by similar developments.

Yet even in modern 'multi-cultural' societies there remains a dominant culture. I have purposely identified my own cultural orientation as 'Anglo-American' to recognize the power of this dominant cultural tradition in American society. There are historic groupings of indigenous and immigrant peoples in the United States that either resist—or are restricted in subtle ways from—complete acculturation into the dominant Anglo-American culture. Also in the Netherlands there is a dominant Dutch-speaking culture, in spite of cultural variations due to regional languages, dissenting religious groupings and immigration. Many articles on multi-cultural societies are rather idealistic and ignore the power of the dominant cultural traditions. Yet even dominant cultures, like immigrant and regional sub-cultures, are not static. Since I have only visited the United States for brief periods over the past 45 years, I recognize that my observations of Anglo-American culture might be somewhat outdated.

Avoiding stereotypes: separating description and evaluation

According to Smith, there is no 'right' or 'wrong' side to any of the six continuums. Rather the model is a vehicle to identify areas of potential tension in relations between people of different cultural groups—between sojourners and immigrants and the people of the dominant culture, and between people of different immigrant and subcultural groups. Because of the brevity of this paper, I have focused on a description of differences without any evaluation of the descriptions presented. I have found that it is important, for building trust relationships with people of other cultures, to initially avoid evaluating the rightness or wrongness of their preferences. The model described in this paper has proved helpful in keeping focused on first understanding differences before proceeding to evaluation of either my own cultural preferences or those of the other person.

However, ‘description is rarely altogether separate from evaluation’ (Nussbaum 1997: 130). And description of cultural differences that never proceeds to an evaluation can leave people just as isolated from each other as when they evaluate each other's cultural preferences too quickly. Description of other cultures without evaluation can lead to 'arcadianism', where we recognize the vices of our own culture, but imagine certain other cultures to be untouched by such vices. In Western cultures this often takes the form of ‘imagining the non-West as paradisiacal, peaceful and innocent, by contrast to a West that is imagined as materialistic, corrupt, and aggressive' (Nussbaum 1997: 134).

In describing the Dutch 'orientation' toward avoiding error through planning and 'warning', I was attempting to get past the usual negative Anglo-American stereotype of Dutch people as 'blunt'. In American idiom, a 'Dutch uncle' is one who is always lecturing or harshly correcting you. The basic values model enabled me to avoid taking personally this Dutch tendency to correction and warning, by giving it a more 'neutral' description. Later, I discovered that this characteristic is the subject of evaluation within the Dutch culture itself.

In an interview, the Dutch Olympic diving champion (1992), Eduard Jongejans said that he would never have made it to his gold medal performance if he hadn't moved to the United States to train. While he was used to his coach only telling him the 'bad news' about his performance, in the USA, he said, the coach tells you the 'good news' first. In 1997, the then Minister of Education, Ritzen, suggested that fewer youth would leave school early if they were complimented more often (Trouw 21-1-97).

Learning to describe the new culture through adaptive participation without evaluation can also lead to a reverse chauvinistic attitude toward one's own culture of origin—especially after a prolonged sojourn in another society. After 40 years of residence in the Netherlands, half of that as a dual citizen (USA/Netherlands), my Anglo-American cultural orientations have undergone substantial changes through interaction with Dutch people, with Moroccan immigrants and with a variety of people of other nationalities. I identify now more with a number of Dutch cultural orientations, and some Moroccan and Canadian ones (because my wife is Canadian). Though I still retain a reasonably strong identification with my nation of origin and my cultural heritage, I find I often become impatient or annoyed with my own Anglo-American culture on visits to the USA, forgetting that this culture has also been changing in different ways than I have over the past 45 years.

Conclusion

There is no simple formula or model for understanding either ones own culture or the culture of other groups of people. Yet growth in understanding is possible. And there are ways to avoid the pitfalls of chauvinism (ethnocentrism), romanticism, arcadianism and skepticism. Retaining an authentic curiosity with a humble character are helpful traits. Recognizing that all cultures are diverse and that none are static are also essential perspectives. However, we need to keep in mind that our understanding of culture will be affected: by the purpose of our study, by our method of analysis, and by our willingness to grow also in self-understanding.

Studying cultures in books or in a classroom may contribute to a conceptual appreciation of other cultures. But cultivation of genuine understanding of other cultures must involve such practical experiences as social adaptation, friendship building and language learning through immersion in another culture. In my experience, people from a dominant culture who live in a multicultural society have greater difficulty in submitting to the painful process of social adaptation than do people from 'minority' cultures. In intercultural encounters, the former are used to other cultures doing the adapting—especially when it comes to which language is used—while the latter are used to having little choice but to adapt. The pain of having to adapt socially to others often produces more quality understanding than any amount of academic curiosity stimulated by the teachers and the tour guides from ones own culture.

The 'basic values' model of Mayers and Smith has proved a helpful tool for practical culture learning where the goal is adaptive participation the culture of another group of people. While it does not present a complete or final picture of a society, it has proved very useful for this Anglo-American sojourner in Dutch society, and fellow newcomer among other immigrant groups in the Netherlands. After 40 years I am still using it to evaluate and adapt my tentative conclusions as I seek to participate in Dutch culture, in the lives of my Canadian in-laws, immigrant neighbors and foreign colleagues—as well as with family and friends in my own continually changing Anglo-American culture.